MEDIA COVERAGE

Radio 1's Morning Ireland

Dundalk devotes exhibition to Arctic Fox

RTE's Nationwide

Exhibition on Dundalk polar explorer

The Franklin Searches

The Franklin Searches I: 1848-1850

The fate of Franklin no man can know

The fate of Franklin no one can tell

Lord Franklin, his men as well

Lady Franklin’s Lament (traditional ballad)

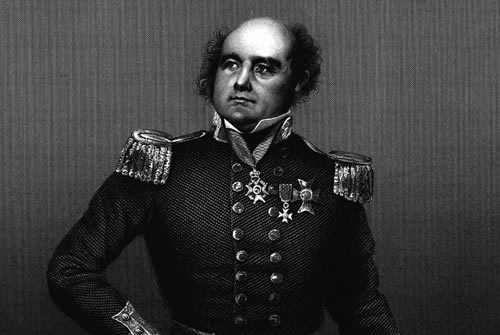

On May 19 1845, Sir John Franklin and a crew of 134 sailors and officers set sail from England, aboard the Erebus and Terror, Arctic-bound to locate and chart the Northwest Passage. It was believed to have been one of the best planned, best prepared and best equipped expeditions ever undertaken by the Navy. When seen off the coast of Greenland on July 19th the men of the Franklin ships were described as being in high spirits; that was the last time that any of the crew was seen alive …

The desire to establish the fate of Franklin rapidly became a cause celebre. At this time McClintock was based in the River Plate in Brazil and had returned to live with his mother (now living in Dublin after his father’s death) before going to study in Portsmouth. This coincided with Sir James Clark Ross’s efforts to recruit a crew to search for Franklin. Through the recommendation of a mutual friend (the Samarang’s Captain William Smyth) McClintock was appointed as second Lieutenant on the Enterprise. Thus in May 1848 the Enterprise and the Investigator set sail bound for the Arctic.

Francis’s participation in this expedition set the tone for his future career allowing him the opportunity to hone those skills for which he would become renowned. In May 1849, he was on one of two sledging parties that explored the areas of Fury Beach and North Somerset. Whilst seeing at first-hand the benefits of sledging he noted the problems of inefficient spirit stoves that resulted in cold food, the problems of inadequate meat reserves and the problem of overly laden sledges.

Despite plans to continue with the search, the threat of a second outbreak of scurvy (which would have had fatal results) forced Captain Ross to set sail for home.

The memories and lessons of his maiden Arctic voyage learnt on this expedition made a lasting impression on McClintock. On first seeing an iceberg, he commented on:

The many beautiful shades which were presented by the constantly changing views of the chasms and channels worn in their sides by the descent of the melting snow called forth our warmest admiration. … they afforded us a truly solemn and imposing spectacle of nature’s workmanship, such as seldom fails to lead one’s thoughts up to the great architect of all things.

The majesty and splendour of the Arctic sights were in stark contrast to the conditions the sledge parties endured. He described the conditions encountered on this trek thus:

Our arrangements for the journey were very simple; our tents covered a space of 6 feet by 9 – just room enough for seven persons to lie down in. … We travelled by night and slept by day, for the double reason of avoiding the intense noonday snow glare and of travelling during the hours when it was too cold to sleep in our tent.

Enduring temperatures that went as low as -49º F he noted that the men

Seem much weakened and have the most ravenous appetites. I do not exaggerate when I say that they could devour at least three times their allowance without inconvenience; and I think double allowance could it possibly be spared, would not by any means be too much for them.

Undoubtedly, whilst homeward bound he began to organise his own thoughts about how such a search should be organised:

We had no fun on this Expedition, Sir James Ross was too scientific and muddled everything. There was scurvy on board when we reached England

McClintock would soon have the opportunity to put his beliefs to the test …